The grands ensembles

were designed by the State and renowned architects to last… And yet we keep demolishing them at great cost.

In the Paris region, the illegal

subdivisions of the 1920s I mentioned yesterday — developed informally, without urban planners — now offer a highly sought-after and fiercely protected living environment.

How can we explain this triple paradox ?

1. The paradox of ultraformal urbanism

After 1945, France faced a severe housing crisis : unsanitary conditions, overcrowding, rural exodus, and demographic growth. The State responded with the grands ensembles program in the 1950s.

The objective : to build massively by standardizing and rationalizing

.

Renowned architects were involved, including winners of the Grand Prix de Rome : Eugène Beaudouin (Cité de la Muette, Drancy), Émile Aillaud (Tours Nuages, Nanterre), Gérard Grandval (Les Choux de Créteil).

But by the 1970s, the model was faltering.

Soon after came the massive demolitions and restructurings we now know.

2. The paradox of informal urbanism

In the 1920s, faced with another housing crisis, agricultural land around Paris was divided and sold cheaply, without roads or infrastructure. By the late 1920s, these areas housed 400’000 people — and 700’000 by the end of the interwar period.

These neighborhoods escaped the 1919 Cornudet Law, which was meant to regulate urban development.

Unlike the grands ensembles, they weren’t designed by experts or optimized. They were built and evolved according to real needs.

Regularized as early as 1934 and serviced after WWII, they are now prized residential neighborhoods under protection.

So much so that almost all evolution and densification is now forbidden !

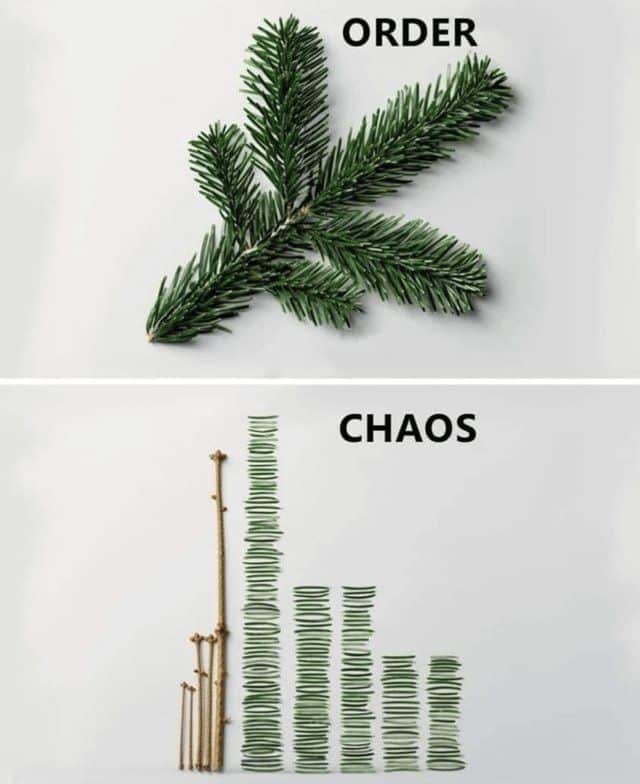

3. The paradox of how planners and architects relate to what escapes our capacity for planning, drawing and rationalization — in other words, to the life

A century later, these once poorly planned

subdivisions are not only a success, they also hold tremendous potential for the future. In 100 years, they have gradually reached a density that remains light : between 15 and 20 dwellings per hectare, as in the example below in Montfermeil.

At the same pace, this density could double over the next 100 years while still remaining village-like (30 to 40 dwellings per hectare), if we implement gentle densification at a rate of 1% per year.

If we consider that the housing needs in Paris Region are urgent, we could go faster and double this density in 50 or even 40 years (2,5% per year).

At the scale of Paris Region, if we don’t freeze these opportunities with rigid local zoning (PLU) regulations — and if we invest in the right engineering to support gentle densification — we’re looking at a potential of 35’000 new homes per year.

That’s half the estimated annual need of 70’000 homes.

gives birthto its own future : plot division as a major art of organic urbanism