We cannot think, build, or regulate a city without anticipating the rebound effects of our actions.

And yet, that is unfortunately what we are increasingly doing each day in France — almost without realizing it…

How did we get here ?

Quite simply, by giving a growing place to morality in urban planning, which gradually

- clusters, around an ideological core, simplistic recipes and actions by assigning them a virtuous status,

- while replacing the more technical, complex, and systemic reasoning, actions, and plans that previously prevailed.

In a word : morality leads to simple action. It is of course useful in many areas of human activity, but in urbanism, we must be cautious with it : because nothing is more complex than a city — or a housing policy.

In practice, thinking of urbanism solely through moral rules amounts to returning to the functionalist urbanism of the 1930s.

At the time, hygienism served as the moral foundation justifying extreme simplification of urban planning — and of the very idea of what constitutes a city.

Remember :

- one space >> one function,

- separation of pedestrian and vehicle flows,

- etc.

Thankfully, we moved away from that !

But now, 100 years later, functionalism is making a comeback — with the green taking the place of hygiene, playing the same role : a sort of moral platform that wraps urban reflections and decisions inside a bubble where (implicitly) planting, greening, and avoiding soil sealing :

- are seen as systematically

virtuous

actions (they would begood actions

in themselves), - and are systematically opposed to other types of action — seemingly contradictory ones — such as welcoming, building, and densifying (which, by symmetry, are almost seen as

bad actions

).

These 2 points are obviously false.

1/ Research has shown, for instance, that tree cover can trap air pollution, preventing it from escaping upward.

2/ Other research has shown that it is possible to both densify and green more — on a small or large scale.

But above all, we are forgetting a fundamental fact :

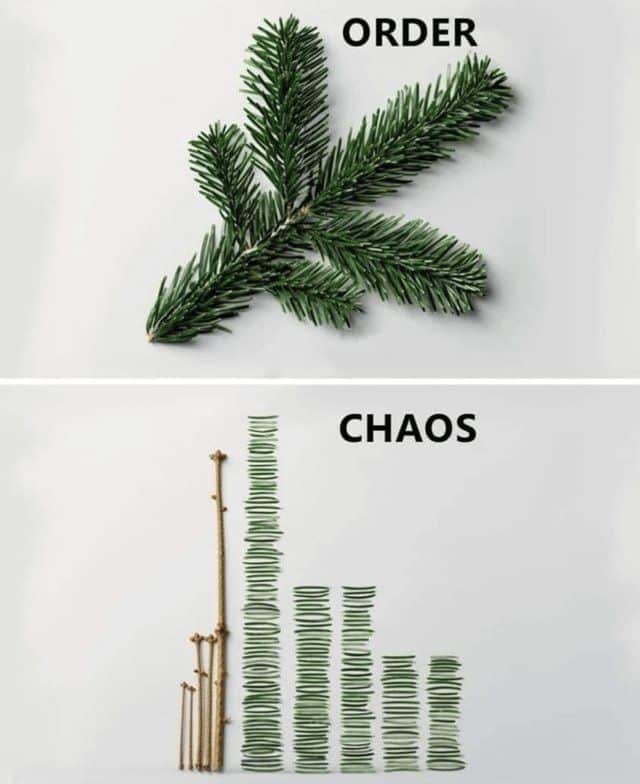

3/ Our actions have first-order effects, and then second-order effects.

The rebound effect should be the first fundamental law of urbanism : since a city is a living organism, acting locally on one given parameter—even if morally glorified, like removing cars from public space or planting trees—leads to effects that go far beyond the first-order impacts.

This is how, as the title of this brilliant Sud Ouest article illustrates, we end up thinking that not building here is virtuous in itself—while forgetting that it will necessarily mean building further away (thus sealing more soil and driving more each day).

Bordeaux Metropolis : Does the ban on new access paths for second-line housing open the door to urban sprawl ?

What if we resisted the simplistic temptation ?

gives birthto its own future : plot division as a major art of organic urbanism